Why the Dollar Dominates, and Why That’s Not All Good

Lack of Rivals to Greenback Keeps It on Top—and Enables U.S.

Government Dysfunction

by David Wessel

In an interview with WSJ’s David Wessel, Cornell’s Eswar Prasad, author of a forthcoming book, “The Dollar Trap: How the U.S. Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance,” explains why the U.S. currency remains so dominant despite all the nation’s woes.

The U.S. was the epicenter of the worst financial crisis in 75 years. Its central bank is printing money at a rate of $1 trillion a year. Its government debt load is huge and its political system is visibly dysfunctional. It represents a shrinking share of the world economy as China and other emerging markets rise.

You’d think the U.S. dollar’s reign as the world’s supreme currency would be ending—or at least vulnerable.

So now comes economist Eswar Prasad with a surprising argument: “The global financial crisis has strengthened the dollar’s prominence in global finance.”

The dollar, he predicts, will remain the world’s reserve currency for a long time. “When the rest of the world wants safety,” he says, “there is no other place to go.”

The dollar, he predicts, will remain the world’s reserve currency for a long time. “When the rest of the world wants safety,” he says, “there is no other place to go.”

Neither the euro nor the Japanese yen is a plausible rival.

China’s yuan may be someday, but not soon. China still lacks the legal and other institutions and deep financial markets that make U.S. Treasury debt so attractive to so many.

Mr. Prasad is no flag-waving naif. He’s a University of Chicago Ph.D. who spent 15 years at the International Monetary Fund, where he did a stint as chief of its China desk. He now splits his time between Cornell University and the Brookings Institution.In a lucid book to be published in February, “The Dollar Trap,” Mr. Prasad argues that the dollar’s persistent dominance is a “suboptimal” reality.

The professor isn’t predicting that the dollar’s value in euros or yen or pounds or yuan will rise inexorably. Like many a card-carrying Ph.D., he sees the size of the U.S. trade deficit and expects the greenback to fall over the long run and eschews predictions about the dollar’s near-term direction.

Mr. Prasad expects China and others to price more of their exports in their own currencies. The yuan recently overtook the euro as the second-most used currency in international trade finance, according to Swift, which runs a major electronic financial pipeline.

But as a safe, secure place to park money, the dollar is stronger than ever. The made-in-America global financial crisis strengthened the dollar’s hold.

Here’s why:

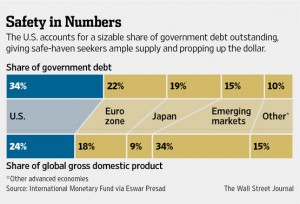

Banks around the world have been ordered by government to hold safe, easy-to-sell assets so they’ll be better equipped for future crises. That adds to demand for government bonds; the U.S. issues more of them than anyone else.

Emerging markets want more safe assets, too. There’s ever-more money sloshing around the globe, much of it moving in and out of emerging markets. That has led them to make two relevant calls:

One, inflows of capital tend to push up exchange rates and threaten exports. So governments are increasingly prone to intervene—that is, to restrain the rise in their currencies by selling them in exchange for foreign currencies. That adds to demand for dollars, which are then invested in U.S. Treasurys.

Two, those same governments have decided it is essential to have a lot of insurance in case foreign capital flees; that means building a big pile of foreign-currency reserves to scare off speculators and to demonstrate they’ve got the

money to pay foreign creditors. That, too, adds to the demand for dollars and U.S. Treasurys.

This demand is occurring at a time when safe assets are in short supply: The Federal Reserve has taken $2.2 trillion of U.S. Treasurys off the market through its bond-buying program. The euro has its issues, and the sovereign debt of some euro-zone members is hardly ultrasafe. Japan and Switzerland have strong institutions and financial markets, but are actively pushing down the value of their currencies; that makes them unappealing as stores of value.

“The entire edifice of global financial stability seems to be built on this fragile foundation: If not the dollar, and if not U.S. Treasury debt, then what?” Mr. Prasad writes.

So what makes this “suboptimal”?

For the U.S., Mr. Prasad says, the global appetite for dollars keeps U.S. interest rates low and makes it easier for the U.S. to pursue foolish budget policies aimed at too much deficit reduction now and too little later.

For other countries, the world’s heavy reliance on dollars makes nearly every economy acutely sensitive to moves (or expectations of moves) by the Fed to increase or decrease the supply of dollars as it tries to steer the U.S. economy. And their stockpiles of dollars exposes them to losses if the dollar’s value

declines, which gives them a reason not to do anything to harm the dollar.

The more angst in the world, the more investors and governments want to hold dollars. This makes the dollar’s dominance “stable and self-reinforcing,” Mr. Prasad concludes.

If the dollar’s role isn’t sturdy—if it is more like a sand pile just a few grains away from collapse—then the world is in trouble. Despite years of yammering, the world hasn’t built an alternative to the U.S. dollar.

Write to David Wessel at capital@wsj.com

© 2013 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. Distribution and use of this material are governed by our Subscriber Agreement and by copyright law.

For non-personal use or to order multiple copies, please contact Dow Jones Reprints at 1-800-843-0008 or visit www.djreprints.com